Walker Carriages

WALKER CARRIAGE COMPANY

By Grace Shackman

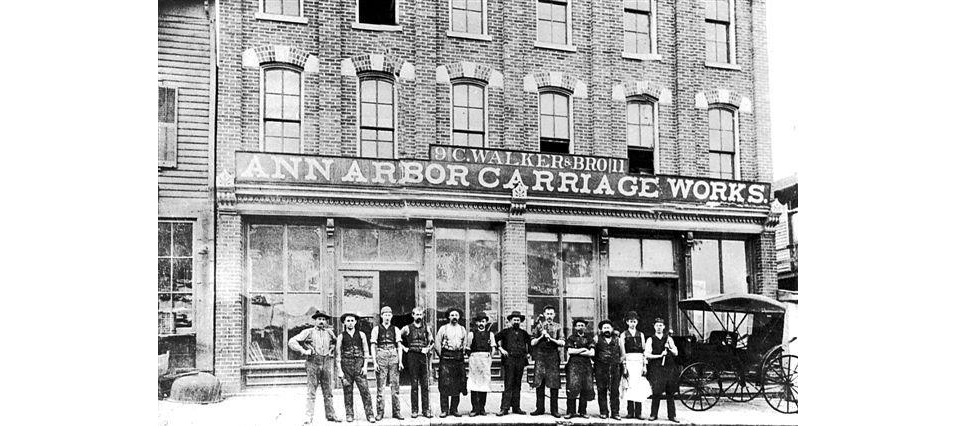

In the 19th Century, when industry was on a much smaller, more local scale, a good-sized county seat like Ann Arbor could be expected to have at least one carriage factory, probably more. Ann Arbor had several. The biggest was Walker and Company's Ann Arbor Carriage works, whose legacy is the handsome red brick building on West Liberty now occupied by the Ann Arbor Art Association.

Walker and Company catered to the high-class end of the carriage trade. U of M regent and publisher Junius Beal would have nothing but a Walker carriage, and Ann Arbor Mayor Samuel Beakes, eager to spread the fame of local products, succeeded in convincing Grover Cleveland's administration to purchase two vehicles from the Ann Arbor Carriage Works. The firm also made more plebian products such as merchants' delivery wagons, simple fire wagons, and spring wagons for farmers taking produce into town. Light sleighs called cutters were made and sold for use in winter months on Ann Arbor's snow-packed streets. Most townspeople, of course, could afford neither the carriage, the cost and feeding of the requisite horse, nor the stable in which to house it. For occasional outings, they would rent a rig from Walker Livery Company, which the Ann Arbor Carriage Works also supplied with vehicles.

Christian Walker founded the carriage factory in 1867 – an opportune time, because Ann Arbor (like most northern towns) experienced great growth in construction, industrial expansion, and general overall wealth in the years just after the Civil War. Within a few years the firm had outgrown its original wooden building on Washington Street, and in 1886 Walker erected the sizable, 7200 square-foot structure now occupied by the Ann Arbor Art Association. A while later the manufacturing area was enlarged by adding an interconnected factory building fronting on Ashley.

Unlike many carriage manufacturers, Walker and Company made each carriage from scratch, from the springs and axles welded in the smith's shop to form the chassis, to the wheels, shafts, and bodies made in the wood-working shop. Leather upholstery and oilcloth tops were put on in the trim shop. The oversize suspension springs that the company used made the Walker carriages relatively easy to identify. Though the showroom had some assembled models on hand for immediate sale, most vehicles, no matter how modest were custom-made according to the purchaser's particular specification in a process that usually lasted four to six weeks. Most of the time went into drying paint.

The working environment at shops like this was a far cry from the automobile factories that supplanted them. Workers specialized in a particular craft-smithing, woodworking, painting, or upholstery. Far from being interchangeable elements in an assembly line, they advanced from apprenticed to skilled craftsmen in careers whose masters commanded a natural respect and authority. In a small shop (Walker and Company employed between 12 to 18 employees), workers were much more likely to feel responsibility and pride for what they made.

The Ann Arbor Carriage Works prospered from the start. Christian Walker lived in an elegant brick Italianate house on the northwest corner of Liberty and Seventh. (It still stands, painted grey and without its porches.)

After Christian Walker's death in 1888, the firm retrenched. It was owned and managed by department head Michael Grossman, master blacksmith Christian Braun, and George Walker, Christian's brother and the head of the wood working shop, who took over sales. They built a new but smaller building on West Liberty, now occupied by a beauty shop, joined it to the Ashley Street factory by a freight elevator, and moved the showroom there, selling the larger Liberty Street building to the Henne and Stanger Furniture Company, which stayed there until the 1950s. An old advertisement painted high on the building's west wall may still be seen: HENNE & STANGER FURNITURE, CARPETS, DRAPERIES, ETC. UNDERTAKING. (Furniture stores often used to be Undertakers as well because they stocked the coffins.)

The carriage company did its best to keep up with changes in transportation. When bikes became popular, Walker's became, according to its advertising, "the most extensive dealer in the city," selling Columbia bicycles. Later, Walker employees used their skills in repairing some of Ann Arbor's earliest automobiles. Walker and Company even produced a few cars for the local gentry, buying the chassis with motor and transmission and then making the bodies.

Carriages, not cars, were what the firm made best, and by 1921 it was clear that carriages had had their day. The three owners were ready to retire anyway, so they decided to close up shop.

In the 19th Century, when industry was on a much smaller, more local scale, a good-sized county seat like Ann Arbor could be expected to have at least one carriage factory, probably more. Ann Arbor had several. The biggest was Walker and Company's Ann Arbor Carriage works, whose legacy is the handsome red brick building on West Liberty now occupied by the Ann Arbor Art Association.

Walker and Company catered to the high-class end of the carriage trade. U of M regent and publisher Junius Beal would have nothing but a Walker carriage, and Ann Arbor Mayor Samuel Beakes, eager to spread the fame of local products, succeeded in convincing Grover Cleveland's administration to purchase two vehicles from the Ann Arbor Carriage Works. The firm also made more plebian products such as merchants' delivery wagons, simple fire wagons, and spring wagons for farmers taking produce into town. Light sleighs called cutters were made and sold for use in winter months on Ann Arbor's snow-packed streets. Most townspeople, of course, could afford neither the carriage, the cost and feeding of the requisite horse, nor the stable in which to house it. For occasional outings, they would rent a rig from Walker Livery Company, which the Ann Arbor Carriage Works also supplied with vehicles.

Christian Walker founded the carriage factory in 1867 – an opportune time, because Ann Arbor (like most northern towns) experienced great growth in construction, industrial expansion, and general overall wealth in the years just after the Civil War. Within a few years the firm had outgrown its original wooden building on Washington Street, and in 1886 Walker erected the sizable, 7200 square-foot structure now occupied by the Ann Arbor Art Association. A while later the manufacturing area was enlarged by adding an interconnected factory building fronting on Ashley.

Unlike many carriage manufacturers, Walker and Company made each carriage from scratch, from the springs and axles welded in the smith's shop to form the chassis, to the wheels, shafts, and bodies made in the wood-working shop. Leather upholstery and oilcloth tops were put on in the trim shop. The oversize suspension springs that the company used made the Walker carriages relatively easy to identify. Though the showroom had some assembled models on hand for immediate sale, most vehicles, no matter how modest were custom-made according to the purchaser's particular specification in a process that usually lasted four to six weeks. Most of the time went into drying paint.

The working environment at shops like this was a far cry from the automobile factories that supplanted them. Workers specialized in a particular craft-smithing, woodworking, painting, or upholstery. Far from being interchangeable elements in an assembly line, they advanced from apprenticed to skilled craftsmen in careers whose masters commanded a natural respect and authority. In a small shop (Walker and Company employed between 12 to 18 employees), workers were much more likely to feel responsibility and pride for what they made.

The Ann Arbor Carriage Works prospered from the start. Christian Walker lived in an elegant brick Italianate house on the northwest corner of Liberty and Seventh. (It still stands, painted grey and without its porches.)

After Christian Walker's death in 1888, the firm retrenched. It was owned and managed by department head Michael Grossman, master blacksmith Christian Braun, and George Walker, Christian's brother and the head of the wood working shop, who took over sales. They built a new but smaller building on West Liberty, now occupied by a beauty shop, joined it to the Ashley Street factory by a freight elevator, and moved the showroom there, selling the larger Liberty Street building to the Henne and Stanger Furniture Company, which stayed there until the 1950s. An old advertisement painted high on the building's west wall may still be seen: HENNE & STANGER FURNITURE, CARPETS, DRAPERIES, ETC. UNDERTAKING. (Furniture stores often used to be Undertakers as well because they stocked the coffins.)

The carriage company did its best to keep up with changes in transportation. When bikes became popular, Walker's became, according to its advertising, "the most extensive dealer in the city," selling Columbia bicycles. Later, Walker employees used their skills in repairing some of Ann Arbor's earliest automobiles. Walker and Company even produced a few cars for the local gentry, buying the chassis with motor and transmission and then making the bodies.

Carriages, not cars, were what the firm made best, and by 1921 it was clear that carriages had had their day. The three owners were ready to retire anyway, so they decided to close up shop.

Grace Shackman's article was published in The Ann Arbor Observer, December, 1982; updated 2008. Reprinted here with permission of the author.

- Webmaster's Note: Author Grace Shackman is an Ann Arbor historian and a history columnist for the Ann Arbor Observer and Community Observer. She is the author of several books, including Ann Arbor in the 19th Century, Ann Arbor in the 20th Century, and Ann Arbor Observed. Saline Area Historical Society reminds our readers that this material is copyright protected. Ms. Shackman graciously made it available online for personal use, only. Neither the article nor any portion of the article may be republished in any form without the author's permission.

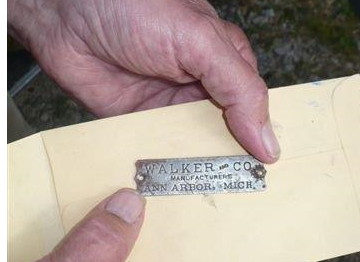

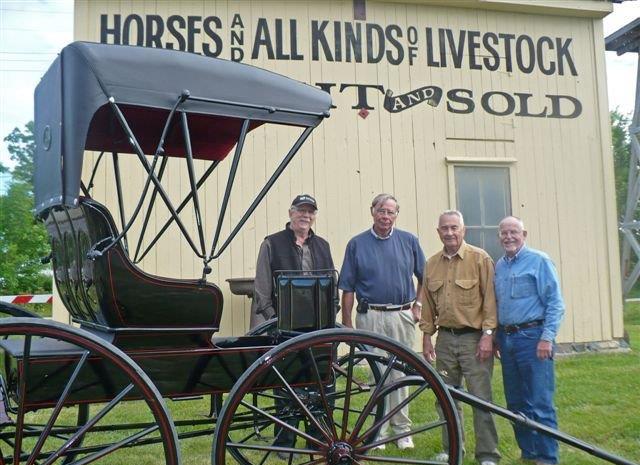

- The Saline Area Historical Society is the proud owner of a Walker Buggy, which we were fortunate to have fully restored by Leroy Martin of Nappanee, IN. Occasionally in good weather, the buggy is part of Saline parades.

- Historic Photo courtesy of Grace Shackman. Depot photos by Robert Lane.