Transportation

From Trail To Highway: The Development of U.S. 12 in Saline, Michigan

By Kathy Holtz

U.S. 12 played an essential part in the settlement and growth of Saline. The highway was a transportation corridor well before white men arrived in this part of the Northwest Territory, or what is now known as southeast Michigan. Changes to U.S. 12 over time reflect the changes in Saline from before its settlement and through its growth to a city with suburban neighborhoods.

Several Indian tribes frequented southeast Michigan; among them were the Potawatomi, the Ojibwa or Chippewa, Ottawa (Odawa), Miami, Fox, and Mascouten. There were no firm boundaries for the natives; warfare and trade caused the tribes and thus their boundaries, to move about. Each tribe had its own type of housing and other structures, local customs, and means of survival, such as agriculture, fishing, or hunting. The abundant natural resources available in the Territory served them well. Some were nomadic; probably all of them traveled various routes to trade furs and other goods with the French (Martinez, 18).

The Indian natives and French traders used the Sauk Trail, which ran from Detroit to the Chicago River. Natives frequented the Saline area because of the legendary salt springs to the south of where the trail crossed the river. The name given to the river, the township, the village, and later, the city was selected because of these salt springs, which originated from a vein of salt reputed to run from Battle Creek to Detroit (Our Pride, 58).

After the War of 1812 the trail became a tactical route from Detroit to Fort Dearborn for moving troops and equipment to locations threatened by Natives, British, or French. In 1824, legislation for the laying out of this Military Road for $3,000 was proposed by Fr. Gabriel Richard, Michigan's delegate in Congress. When it passed, the commissioners named to conduct the survey hired Orange Risdon to do the work.

Orange Risdon surveyed the Military Road from 1824-1827 and was impressed with what he saw in the Saline area. In August of 1824, Risdon bought 120 acres in the NE quarter of Section 1 of what is now Saline Township, and continued his surveying. In 1829, he came back to settle, platted the village on part of his land, and named it Saline after the river and newly formed

Saline Township (Collins, 3).

Willis Dunbar says that

"..these roads were a far cry from their modern counterparts. It can hardly be said that they were "built" at all, as we think of highway building today. Surveyors selected the route, often following Indian trails, axemen cut away the brush and felled trees low enough along the path so wagons could pass over the stumps, and workmen constructed crude bridges over streams which could not easily be forded. Logs were laid crosswise of the road across bogs and swamps to prevent wagons and animals from miring. This was known as a "corduroy road." Other than this, little was done to provide a surface for the roads. They were notoriously bad. (Dunbar, 191. Used with permission.)

According to the late Bessie Carven Collins, local historian, corduroy roads were terribly rough. With the introduction of the sawmills, road composition was updated from half logs to massive planks, about 16 inches wide and 8 feet long, and 3 inches thick. They were privately financed but chartered by the state, so that a toll was charged for their use. Several tollhouses existed around Saline; one toll house was incorporated into the larger Ruckman family farmhouse on Macon Road (Proctor, 39).

As folks settled in the region, businesses sprang up along the Old Chicago Road, or the Chicago Turnpike. Among them were several hotels in Saline: the American House built in 1833, the Saline Exchange Hotel built in 1834 and the Halfway Inn, located about five miles west of Saline, and which had facilities to provide for travelers and horses. Other businesses began, such as gristmills, sawmills, hardware and general stores, harness shops, blacksmith shops, and liveries, among many.

U.S. 12 played an essential part in the settlement and growth of Saline. The highway was a transportation corridor well before white men arrived in this part of the Northwest Territory, or what is now known as southeast Michigan. Changes to U.S. 12 over time reflect the changes in Saline from before its settlement and through its growth to a city with suburban neighborhoods.

Several Indian tribes frequented southeast Michigan; among them were the Potawatomi, the Ojibwa or Chippewa, Ottawa (Odawa), Miami, Fox, and Mascouten. There were no firm boundaries for the natives; warfare and trade caused the tribes and thus their boundaries, to move about. Each tribe had its own type of housing and other structures, local customs, and means of survival, such as agriculture, fishing, or hunting. The abundant natural resources available in the Territory served them well. Some were nomadic; probably all of them traveled various routes to trade furs and other goods with the French (Martinez, 18).

The Indian natives and French traders used the Sauk Trail, which ran from Detroit to the Chicago River. Natives frequented the Saline area because of the legendary salt springs to the south of where the trail crossed the river. The name given to the river, the township, the village, and later, the city was selected because of these salt springs, which originated from a vein of salt reputed to run from Battle Creek to Detroit (Our Pride, 58).

After the War of 1812 the trail became a tactical route from Detroit to Fort Dearborn for moving troops and equipment to locations threatened by Natives, British, or French. In 1824, legislation for the laying out of this Military Road for $3,000 was proposed by Fr. Gabriel Richard, Michigan's delegate in Congress. When it passed, the commissioners named to conduct the survey hired Orange Risdon to do the work.

Orange Risdon surveyed the Military Road from 1824-1827 and was impressed with what he saw in the Saline area. In August of 1824, Risdon bought 120 acres in the NE quarter of Section 1 of what is now Saline Township, and continued his surveying. In 1829, he came back to settle, platted the village on part of his land, and named it Saline after the river and newly formed

Saline Township (Collins, 3).

Willis Dunbar says that

"..these roads were a far cry from their modern counterparts. It can hardly be said that they were "built" at all, as we think of highway building today. Surveyors selected the route, often following Indian trails, axemen cut away the brush and felled trees low enough along the path so wagons could pass over the stumps, and workmen constructed crude bridges over streams which could not easily be forded. Logs were laid crosswise of the road across bogs and swamps to prevent wagons and animals from miring. This was known as a "corduroy road." Other than this, little was done to provide a surface for the roads. They were notoriously bad. (Dunbar, 191. Used with permission.)

According to the late Bessie Carven Collins, local historian, corduroy roads were terribly rough. With the introduction of the sawmills, road composition was updated from half logs to massive planks, about 16 inches wide and 8 feet long, and 3 inches thick. They were privately financed but chartered by the state, so that a toll was charged for their use. Several tollhouses existed around Saline; one toll house was incorporated into the larger Ruckman family farmhouse on Macon Road (Proctor, 39).

As folks settled in the region, businesses sprang up along the Old Chicago Road, or the Chicago Turnpike. Among them were several hotels in Saline: the American House built in 1833, the Saline Exchange Hotel built in 1834 and the Halfway Inn, located about five miles west of Saline, and which had facilities to provide for travelers and horses. Other businesses began, such as gristmills, sawmills, hardware and general stores, harness shops, blacksmith shops, and liveries, among many.

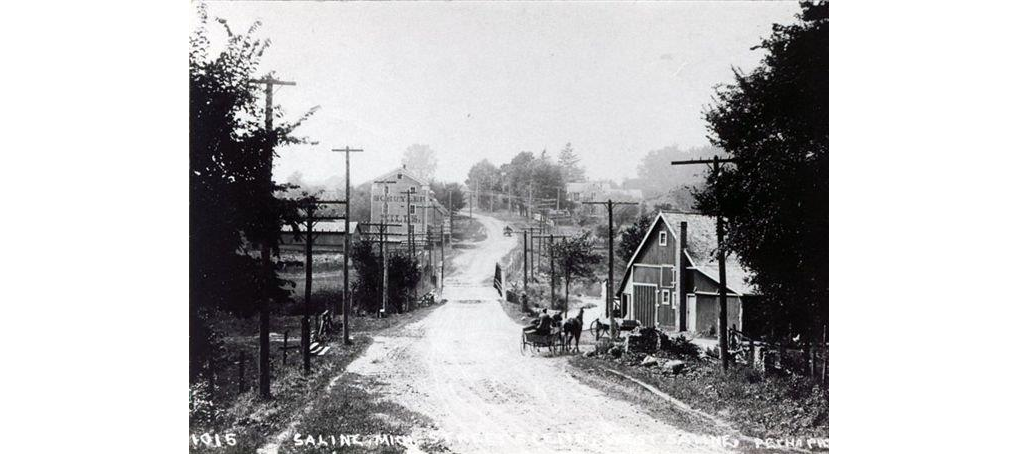

West on Chicago Turnpike

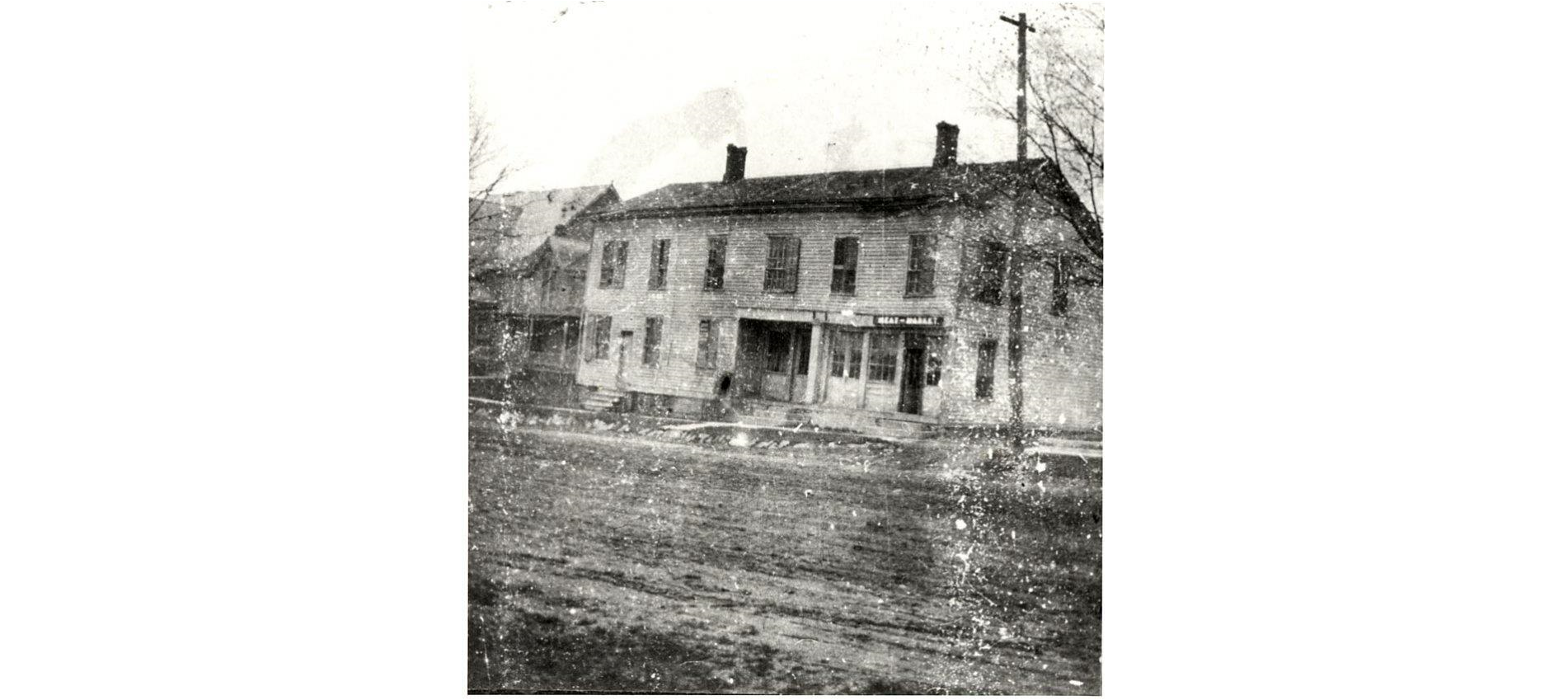

Saline Exchange Hotel

Maintenance of U.S. 12 did not take place with asphalt patching crews because the roads were unpaved. The dirt roads were smoothed with a large horse-drawn grader that had a blade like that of a small snow plow. In warmer weather, a horse-drawn wagon with a water tank aboard was used to wet down the road in order to minimize dust. The water tank was filled at the Saline River. Note the unpaved U.S. 12 in front of the Saline Exchange Hotel.

With the introduction of the railroad into Saline in 1870, a new way of life began which drastically altered travel habits. Stagecoach routes were abandoned, causing inns along the Chicago Road to shut down; both the Saline Exchange and the American House closed their doors and became residences. A newer hotel called the Harmon House was built in the 1860s and remained Saline's only inn. In 1927, Henry Leutheuser bought the renamed Saline Hotel and built his restaurant in front of it; his business and buildings remained until the 1960s.

A convenient and exciting change occurred when a branch of the interurban was extended into Saline from the east in 1899. The trolley, known as "Old Maude," gave travelers the opportunity to go to nearby cities every two hours from morning until midnight. Tracks were built along U.S 12 as far west as the cemetery. A waiting room was available at the Unterkircher building, which still stands at the east half of 112 E. Michigan Ave. where the barber shop is located. The power substation for Old Maude was located on the site of the present-day fire station, at 201 E. Michigan Avenue. It was similar to a station that still stands on the northwest corner of Jackson and Lima Center Roads in Lima Township.

Gradually, a new form of transportation became ordinary: the automobile. Autos began to appear with more and more regularity along U.S. 12 and when the interurban was still operating, car drivers were known to race with Old Maude, just for fun. It became a bit of a game, and the trolley drivers would jot down the car license plate numbers on Old Maude's motor block (Collins, 13).

On one occasion, this act helped solve a murder mystery. On a morning of July 15, 1921, a double murder was committed south of Saline on Milan Road, where three Burg sisters lived with their brother George. Stories had circulated that they were an affluent family that kept their wealth hidden on the property (Collins, 13).

On that particular morning, Mr. Burg was working in a barn with a neighbor when a large automobile with several male passengers drove into the farmyard. They asked for water and one of the sisters directed them to get a pail and fill it at the pump. One of the men filled a bucket and poured the water over a tire on the car and then they left. After a short interval, they drove back to the farm a second time, stayed a short while, and departed. Mr. Burg and his neighbor Henry Folmer, were later found dead of gunshot wounds.

During the investigation, one deputy thought to ask Old Maude's motorman of that day if he had seen a large auto along the route. He said that he had; the noted license number was traced to a Cadillac in Detroit and the murderers were found in the Italian quarter. The two murderers received life sentences (Collins, 15).

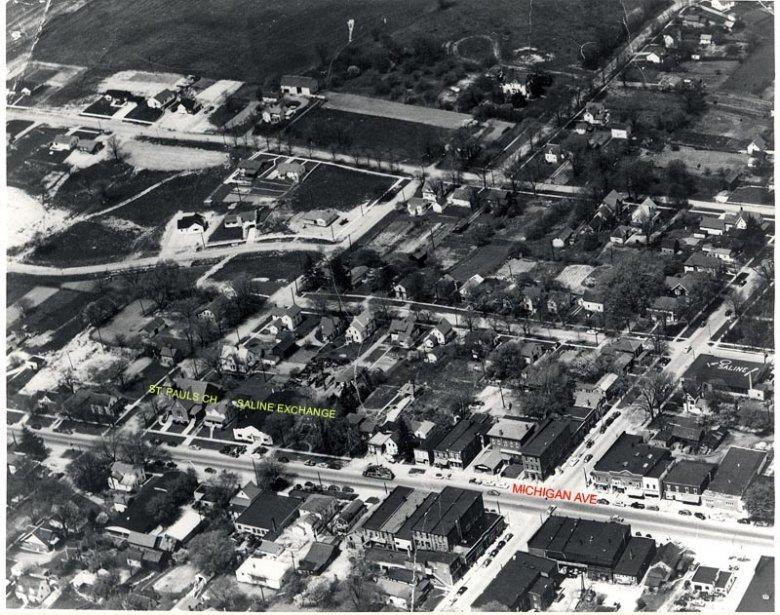

George Cook was a deputy sheriff at the time of the murder and a figure in the automobile world of Saline as well. He became involved in the transportation business around 1912, when he operated a livery and transport service. Later, he transferred into auto sales, becoming a Chevrolet agent around 1918, and opened the Saline Garage. Archival photos reveal that his garage was located on the site of the Saline Exchange Hotel. It is significant that two business buildings on this site served the traveler; one in the 19th and the other in the 20th century. In the aerial photo below, the concrete-block Saline Garage is located two lots east of St. Paul's Church.

Other car dealerships and new gas stations began to appear in the 1910s and 20s. George Uphaus began selling gasoline for 50 cents for five gallons around 1915 (Proctor, 38). Weidman's Ford dealership featured a small gas station west of the showroom, in what is now an alley between 118 and 112 E. Michigan Ave. Weidman's dealership was in the portion of the R&B building with three pilasters, or brick vertical protrusions. Steeb Dodge began at the location of the Heininger and Heininger Farm Implements business at 121 W. Michigan Avenue, and though the address has changed, the dealership has expanded at the same location since that time. According to Jack Steeb, gas stations were plentiful along U.S. 12 by the 1920s and 30s.

With the introduction of the railroad into Saline in 1870, a new way of life began which drastically altered travel habits. Stagecoach routes were abandoned, causing inns along the Chicago Road to shut down; both the Saline Exchange and the American House closed their doors and became residences. A newer hotel called the Harmon House was built in the 1860s and remained Saline's only inn. In 1927, Henry Leutheuser bought the renamed Saline Hotel and built his restaurant in front of it; his business and buildings remained until the 1960s.

A convenient and exciting change occurred when a branch of the interurban was extended into Saline from the east in 1899. The trolley, known as "Old Maude," gave travelers the opportunity to go to nearby cities every two hours from morning until midnight. Tracks were built along U.S 12 as far west as the cemetery. A waiting room was available at the Unterkircher building, which still stands at the east half of 112 E. Michigan Ave. where the barber shop is located. The power substation for Old Maude was located on the site of the present-day fire station, at 201 E. Michigan Avenue. It was similar to a station that still stands on the northwest corner of Jackson and Lima Center Roads in Lima Township.

Gradually, a new form of transportation became ordinary: the automobile. Autos began to appear with more and more regularity along U.S. 12 and when the interurban was still operating, car drivers were known to race with Old Maude, just for fun. It became a bit of a game, and the trolley drivers would jot down the car license plate numbers on Old Maude's motor block (Collins, 13).

On one occasion, this act helped solve a murder mystery. On a morning of July 15, 1921, a double murder was committed south of Saline on Milan Road, where three Burg sisters lived with their brother George. Stories had circulated that they were an affluent family that kept their wealth hidden on the property (Collins, 13).

On that particular morning, Mr. Burg was working in a barn with a neighbor when a large automobile with several male passengers drove into the farmyard. They asked for water and one of the sisters directed them to get a pail and fill it at the pump. One of the men filled a bucket and poured the water over a tire on the car and then they left. After a short interval, they drove back to the farm a second time, stayed a short while, and departed. Mr. Burg and his neighbor Henry Folmer, were later found dead of gunshot wounds.

During the investigation, one deputy thought to ask Old Maude's motorman of that day if he had seen a large auto along the route. He said that he had; the noted license number was traced to a Cadillac in Detroit and the murderers were found in the Italian quarter. The two murderers received life sentences (Collins, 15).

George Cook was a deputy sheriff at the time of the murder and a figure in the automobile world of Saline as well. He became involved in the transportation business around 1912, when he operated a livery and transport service. Later, he transferred into auto sales, becoming a Chevrolet agent around 1918, and opened the Saline Garage. Archival photos reveal that his garage was located on the site of the Saline Exchange Hotel. It is significant that two business buildings on this site served the traveler; one in the 19th and the other in the 20th century. In the aerial photo below, the concrete-block Saline Garage is located two lots east of St. Paul's Church.

Other car dealerships and new gas stations began to appear in the 1910s and 20s. George Uphaus began selling gasoline for 50 cents for five gallons around 1915 (Proctor, 38). Weidman's Ford dealership featured a small gas station west of the showroom, in what is now an alley between 118 and 112 E. Michigan Ave. Weidman's dealership was in the portion of the R&B building with three pilasters, or brick vertical protrusions. Steeb Dodge began at the location of the Heininger and Heininger Farm Implements business at 121 W. Michigan Avenue, and though the address has changed, the dealership has expanded at the same location since that time. According to Jack Steeb, gas stations were plentiful along U.S. 12 by the 1920s and 30s.

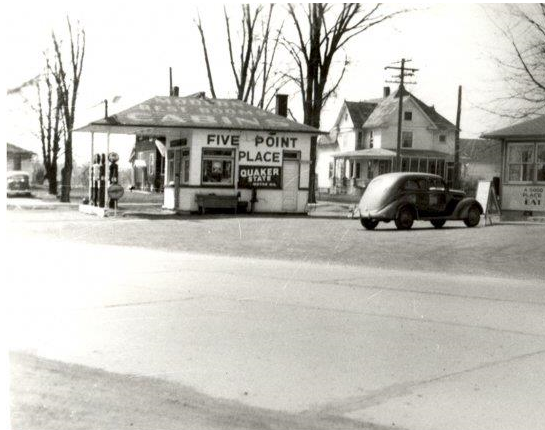

Five Points

Another business that opened because of automobile travel through Saline was Chris and Lydia Volz's Five Point Place at the northeast corner of Maple and U.S. 12. They bought the business with a gas station on the site in 1930, and later built a lunchroom and seven overnight tourist cabins. An overnight stay in a cabin cost $5; their delicious Chicken Barbeque was 50 cents.

Kenny Volz said that his mother worked from 7:00 a.m. until 10:00 at night, after which time she began making pies for the next day's sales. After they sold the business in the 1950s, the cabins were moved off the property. The lunchroom met its sad and ironic demise in the 1960s when a tractor- trailer jackknifed and smashed into it.

Among the numerous names given to Michigan Avenue was U.S. Hwy. 112. From approximately the 1920s until 1960, U.S.12 began in Detroit at Plymouth Road, went into Ann Arbor, and then west on Jackson Road, following the present-day interstate I-94 route very closely across the state.

During those early years, the U.S. 12 of today was known as U.S. 112. According to Gladys Saborio, member of the Heritage Trail Council, the Old U.S. 12 lost its U.S. highway designation when the I-94 opened in 1960. It was at that same time that U.S. 112 became U.S.12, and the "112" figure became obsolete.

Physical changes occurred to U.S.12 in Saline in the 1960s. It remained a two-lane highway in the early 1960s, but by the late 1960s was a five lane road from the Rentschler Farm heading west through town. In 2002, the road was widened on the west side of town. Similarly, the U.S. 12 Bridge over the Saline River has undergone several physical changes. In the early 20th century, it was composed of steel trusses, in the 1940s it was a concrete camel-back structure, and by 1968, it had a lower metal bar railing. Today it is three lanes wide, with combination concrete and metal rails.

Henry Ford took an interest in Saline during the episode of Village Industries, which he developed to connect agriculture with industry. He bought the Schuyler Mill in 1937, moved it back from U.S. 12 by about 30 feet, and built his soybean extraction plant behind it to the south. Oil from the soybeans was used in paints and automobile parts. Ford also took an interest in education late in his life. He bought the Hoyt School on Macon Road in 1943 and had it reconstructed at its present location across from the former Schuyler Mill (now Weller's), at 600 W. Michigan Ave. It was then used for the education of the children of Ford's Village Industry employees. Both the soybean operation and the school closed in 1947.

Changes in the landscape around Saline occurred with the infiltration of manufacturing, as illustrated in the 1960s when the Ford Plant was built along U.S. 12. on former farmland between the Rentschler and Morton Farms. A flagpole at the Busch's Shopping Center presently marks the location of the Morton farmhouse and a realtor's office occupies the building that was once a large chicken house on the farm. Rentschler Farm buildings, though now surrounded by development, serve as a farm museum for the Saline Area Historical Society.

The rumbling of trucks and the roar of traffic is heard 24 hours a day on U.S. 12 in Saline as this vital transportation route continues to serve the Great Lakes region. U.S. 12 is part of the MotorCities National Heritage Area, an arm of the National Park Service, as well as a Heritage Trail. Though it may look like an ordinary highway, it is a road with a varied past. Awareness of the history of Michigan Avenue helps give us a sense of who we are and what we've come from (and what the road itself has come from); it connects us with the larger historical picture and gives us a sense of place and identity. Undeniably, U.S. 12 is fundamental to Saline history.

Author's Note: Photographs referred to in this article can be found at http://saline.lib.mi.us/sbfg/saline. Proceed to the Historical Photos of Saline link, and then below the Search link, click on "Browse all Images." References to specific photograph numbers are found below:

Photo number 374 shows Orange Risdon's map of SE Michigan and includes the Old Chicago Road.

Township horse-drawn road grader: photo 293.

Horse-drawn water tank: photo 318.

Old Maude: photos 13, 14, 184.

Unterkircher building: photo 132.

Interurban Substation: photo 4.

Dam and Curtiss Park: Photos 3, 8, 9, 210-210c.

Hoyt-Ford School: photo 209.

Aerial Photo of Ford Plant and Rentschler and Morton Farms: photo 350.

Kenny Volz said that his mother worked from 7:00 a.m. until 10:00 at night, after which time she began making pies for the next day's sales. After they sold the business in the 1950s, the cabins were moved off the property. The lunchroom met its sad and ironic demise in the 1960s when a tractor- trailer jackknifed and smashed into it.

Among the numerous names given to Michigan Avenue was U.S. Hwy. 112. From approximately the 1920s until 1960, U.S.12 began in Detroit at Plymouth Road, went into Ann Arbor, and then west on Jackson Road, following the present-day interstate I-94 route very closely across the state.

During those early years, the U.S. 12 of today was known as U.S. 112. According to Gladys Saborio, member of the Heritage Trail Council, the Old U.S. 12 lost its U.S. highway designation when the I-94 opened in 1960. It was at that same time that U.S. 112 became U.S.12, and the "112" figure became obsolete.

Physical changes occurred to U.S.12 in Saline in the 1960s. It remained a two-lane highway in the early 1960s, but by the late 1960s was a five lane road from the Rentschler Farm heading west through town. In 2002, the road was widened on the west side of town. Similarly, the U.S. 12 Bridge over the Saline River has undergone several physical changes. In the early 20th century, it was composed of steel trusses, in the 1940s it was a concrete camel-back structure, and by 1968, it had a lower metal bar railing. Today it is three lanes wide, with combination concrete and metal rails.

Henry Ford took an interest in Saline during the episode of Village Industries, which he developed to connect agriculture with industry. He bought the Schuyler Mill in 1937, moved it back from U.S. 12 by about 30 feet, and built his soybean extraction plant behind it to the south. Oil from the soybeans was used in paints and automobile parts. Ford also took an interest in education late in his life. He bought the Hoyt School on Macon Road in 1943 and had it reconstructed at its present location across from the former Schuyler Mill (now Weller's), at 600 W. Michigan Ave. It was then used for the education of the children of Ford's Village Industry employees. Both the soybean operation and the school closed in 1947.

Changes in the landscape around Saline occurred with the infiltration of manufacturing, as illustrated in the 1960s when the Ford Plant was built along U.S. 12. on former farmland between the Rentschler and Morton Farms. A flagpole at the Busch's Shopping Center presently marks the location of the Morton farmhouse and a realtor's office occupies the building that was once a large chicken house on the farm. Rentschler Farm buildings, though now surrounded by development, serve as a farm museum for the Saline Area Historical Society.

The rumbling of trucks and the roar of traffic is heard 24 hours a day on U.S. 12 in Saline as this vital transportation route continues to serve the Great Lakes region. U.S. 12 is part of the MotorCities National Heritage Area, an arm of the National Park Service, as well as a Heritage Trail. Though it may look like an ordinary highway, it is a road with a varied past. Awareness of the history of Michigan Avenue helps give us a sense of who we are and what we've come from (and what the road itself has come from); it connects us with the larger historical picture and gives us a sense of place and identity. Undeniably, U.S. 12 is fundamental to Saline history.

Author's Note: Photographs referred to in this article can be found at http://saline.lib.mi.us/sbfg/saline. Proceed to the Historical Photos of Saline link, and then below the Search link, click on "Browse all Images." References to specific photograph numbers are found below:

Photo number 374 shows Orange Risdon's map of SE Michigan and includes the Old Chicago Road.

Township horse-drawn road grader: photo 293.

Horse-drawn water tank: photo 318.

Old Maude: photos 13, 14, 184.

Unterkircher building: photo 132.

Interurban Substation: photo 4.

Dam and Curtiss Park: Photos 3, 8, 9, 210-210c.

Hoyt-Ford School: photo 209.

Aerial Photo of Ford Plant and Rentschler and Morton Farms: photo 350.

- For more information on historic routes, events, and sites concerning Automobile Heritage in Michigan, click on www.experienceeverythingautomotive.org.

- Clements, Wayne, Rick Kuss, and Cindy Janecke. Founders Week. Saline Area Historical Society. 2001.

- Collins, Bessie Carven. "The History of Transportation in Saline". Paper presented at a meeting in the new Saline Savings Bank. Saline, May 26, 1964.

- Dunbar, Willis F. Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State. Revised Ed. by George S. May. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 1965, 1970. Revised Ed. 1980. pp.190-191.

- Gulf Michigan Touring Map. Michigan Department of Conservation, Lansing; Southeast Michigan Tourist and Publicity Association, Detroit; East Michigan Tourist Association, Bay City; Upper Peninsula Development Bureau, Marquette; West Michigan Tourist and Resort Association, Grand Rapids. c. 1955. Eastern Michigan University Map Library.

- Kosky, Susan. Images of America: Saline. Charleston SC, Portsmouth NH, San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, an imprint of Tempus Publishing, Inc. 2003.

- Martinez, Charlie. "The Indians." A History of Oakland County. Ed. Arthur Hagman. Pontiac, MI: Oakland County Sesqui-Centennial Committee, 1970. pp.14-19.

- Michigan: A Guide to the Wolverine State. American Guide Series, Illustrated. Michigan State Administration Board: Statewide sponsors of the Michigan Writer's Project, WPA. New York: Oxford University Press. 1941.

- Michigan State Highway Department. Five Year Program-Progress: July 1, 1957-July 1, 1962. (Map of expressway construction progress.) Michigan State Highway Department, John C. Mackie, Commissioner. December 31, 1958. Eastern Michigan University Map Library.

- Michigan State Highway Department. 1941 Official Michigan Highway Map. G. Donald Kennedy, State Highway Commissioner, Lansing, Michigan. Spring edition, 1941, March 21st Issue. Prepared by Rand-McNally & Company, Chicago, IL. Eastern Michigan University Map Library.

- "Old Salt Well Has Been Found." Saline Observer 8 June 1944. Reprinted in Our Pride. Saline-Brecon Friendship Guild, Ltd. 1991: p.58.

- Proctor, Hazel. Old Saline Village. Prepared for the City of Saline by Ann Arbor Federal Savings, 1975.

- Saline Historic District Commission, "Growth of Saline." Our Pride, Saline, Michigan, 1991. pp. 22-24.

- Video Tape: "A History of Saline 1820-1966." Written and directed by Al Eicher. The Saline Area Historical Society, the Saline Area Chamber of Commerce, and Saline Historic District Commission. Program Source International. c. 1997.